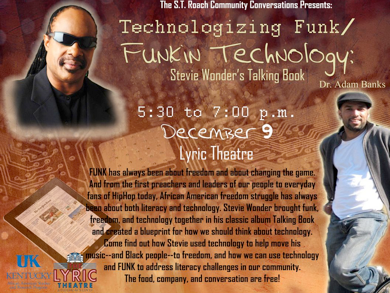

Dr. Adam J. Banks, Associate Professor of Writing, Rhetoric, and Digital Media, University of Kentucky

AB Off Campus

Dr. Adam J. Banks, Associate Professor of Writing, Rhetoric, and Digital Media, University of Kentucky

AB Off Campus

Here’s the closest thing to an official “bio” that I can give you...

Cerebral and silly, outgoing and a homebody, a little melancholy and a lot of joy, more slow jam than HipHop, but that, and some blues and some jazz too. A committed teacher, in love and hate with writing and enjoying the struggle. Vernacular and grounded like Langston and Jook Joints, but academic and idealistic too. Convinced that Donny Hathaway is the most compelling artist of the entire soul era, and that we *still* don't give Stevie Wonder and Patrice Rushen enough love.

Born and raised in Cleveland, Ohio, and educated in the Cleveland Public Schools (when they were public and not "municipal"), Adam Banks received his BA in English from Cleveland State University and his MA and PhD from Penn State University. Formerly an Associate Professor of Writing and Rhetoric at Syracuse University, Banks served as the 2010 Langston Hughes Visiting Professor of English at the University of Kansas and is currently on the Writing, Rhetoric, and Digital Media faculty at the University of Kentucky. His teaching and research interests include African American rhetoric, digital media, social and cultural issues in technology, community literacies and engagement, and rhetoric and composition theory and pedagogy.

He is the author of Race, Rhetoric, and Technology: Searching for Higher Ground, a book challenging teachers and scholars in writing and technology fields to explore the depths of Black rhetorical traditions more thoroughly and calling African Americans, from the academy to the street, to make technology issues a central site of struggle. This debut book was reviewed in 4 major journals and awarded the 2007 Computers and Composition Distinguished Book Award. His current book, Digital Griots: African American Rhetoric in a Multimedia Age, was released this spring by Southern Illinois University Press.

Turn Off The Lights So I Can See: The Last True Black Music

this is an old piece--almost 10 years old now, and completely nonacademic, but I’m including it here since I still describe myself as more slow jam than hip hop...

The image of young love—intense desire, mostly innocent, and no knowledge of what to do with it anyway—in the basement of somebody’s house party might be too easy a place to start a tribute to black folk and the tradition of the slow jam. Even if all that nervous energy in the dank corners too near somebody’s washing machine is the hallowed ground where many of us were initiated into Experience. It’s just too clean—the slow jam is so

important because of the range it covers—from first love to last lay to the pain of being too far from either and a need to hold and be held. And let go of everything that we hold too tightly. Love, lust, want, need, shouted pain and silent joy—the slow jam is holy because it is pure and it is funk.

It is the one place we take off the mask.

As powerful as other traditions are in our music—Bre’r Rabbit himself lives in the genius and the game of blues,jazz, and hip-hop—the space of the black love song is different. Just as Bugs Bunny colonized and sanitized ourfables, mainstream America has found ways to live in almost all those other traditions. The gaze that makes the mask hasfound some of that genius. The slow jam is different. People could learn to jitterbug and break dance here at home, and even slow dance, but still not come close to that place we go when the lights go down. As commodified as all our other music has become, even abroad, we know they ain’t playin Creepin’ or slow draggin to Reasons in the clubs in France—and we know the French used to love them

some things Negro.

But even more, no matter who remakes it, no one else can step inside—or even claim to—this part of our music. Try as much as you want to get up under or into Donny Hathaway’s (or the Temptations’) version of A Song for You. The depth is too vast, the pain too close to that jagged edge others have taken from our music and gone. You can’t steal Donny, or Black Moses, or Aretha. Or Sam Cooke or Minnie or Marvin or Patti. Or the Isleys or Prince or David Ruffin. Not even D’Angelo’s young funk. Cover the lyrics, copy the notes, rip the chord progressions all you want and leave with an empty musical bag if that space has not been your home.

Of course, much of the same holds for all black music. It never was the whole blues that Hughes’ cultural criminals slid into their swing mikados. But the tradition of the slow jam has somehow remained insular, even while Bootsy sells pizza and Dre sells Eminem and white boys cram blues conferences claiming knowledge of the origins of our music and argue for an “autonomous white blues tradition”. Now, love never offers safe space. But this insularity has made the slow jam the place of engagement in black music. The place where we could gather up our pieces and give us back to each other whole.

No matter what madness is going on in the rest of our music, no matter how we hide our wounds from the rest of the world—and sometimes reveal even more in the hiding—the reconstruction starts in the love song. I guess having your mind blown is good for honesty. The unaffected cool that Miles gave birth to is in us somewhere, but not here. The hoochie coochie man and his grandson the Playa have been dropped, even if only for a while when Eddie Levert is shoutin "I'm caught like a fish...". The baaad blues woman is still around somewhere, but not here. And the ice-flossin, donut turning Willies and objectified, booty-shakin dancers of the videos are definitely gone. But the slow jam deals with all of the pain, complexity, and so-called reality that these genres are given so much credit for examining. Whatever postures we develop, we’re forced to come correct in the slow jam. We gather up the pieces of who we really are, or who we really want to be. And we give them both openly, freely.

That is why it is holy. And probably why we always talking about God and Sex on the same albums, on the same sides, in the same songs. But sanctified spaces don’t help much when they don’t last, or when somebody else is posting settlements in them. Even more impressive about this space is this: the slow jam, the slow drag, the intense

ballad spans the almost the whole tradition of our music and still hasn’t been touched. Black music has been jacked and stripped down in all kinds of places in American and world culture, but this remains. Singularly. Ours. It lives in the blues, in jazz, in soul, in r&b, in funk, in hip hop. The divas sung it, the bluesmen and women cried it, Barry begged it. Even wannabe crooners put aside sappy visions of pie in the sky romance and got down into it too, as we all know Marvin did. Aretha came out of the church and made us feel it. And of course many made them their calling, their special place in the music, like the early “Lufa”.

Maybe that basement house party is the right place to start, with that love that came before the mask. As long as we add the jook joint, the nightclub, the back seat of somebody’s car, the park, the other woman’s and the other man’s house, and the payphones where we beg, talk, love, go, come, hate, break up, get together, tear ourselves up, and make each other whole again.

Some semi-random shouts to everyday folk and scholars who continue to shape who I be, and who I’m trying to become...

Keith Gilyard

Geneva Smitherman,

the Queen Mother

Donna Whyte

Frank Adams

Wanda Coleman

Ray Winbush

Pam Charity

Lorenzo Smart

Chuck Jones

Kookie Harley

Ife Nellons

Jackie Grace

Valarri Flanagan

Janet Bennet

Karen Stanislaus-Fung

Rev. Daren Jaime

George Kilpatrick

Gwen Pough

Don Sawyer

Omanii Abdullah

Frank X Walker

Nikky Finney

Arthur Flowers

Alesia Alexander Layne

Dr. Rick Wright

Lorraine Ford

Cedric Bolton

Latoya Sawyer

James Cone

Jawwaad Rasheed

Elaine Richardson

MaryEmma Graham

Edgar Tidwell

who i be: a committed teacher; a midnight believer; saturday night *and* sunday morning; a slow jam in a hiphop world